Today in IS 302 we viewed the video “Can the UN Keep the Peace”, which looked at the challenges that face the UN Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like the pairing of the perfect wine with the right meal, this video was (at least in my opinion) a perfect complement to today’s readings.

Category: Africa

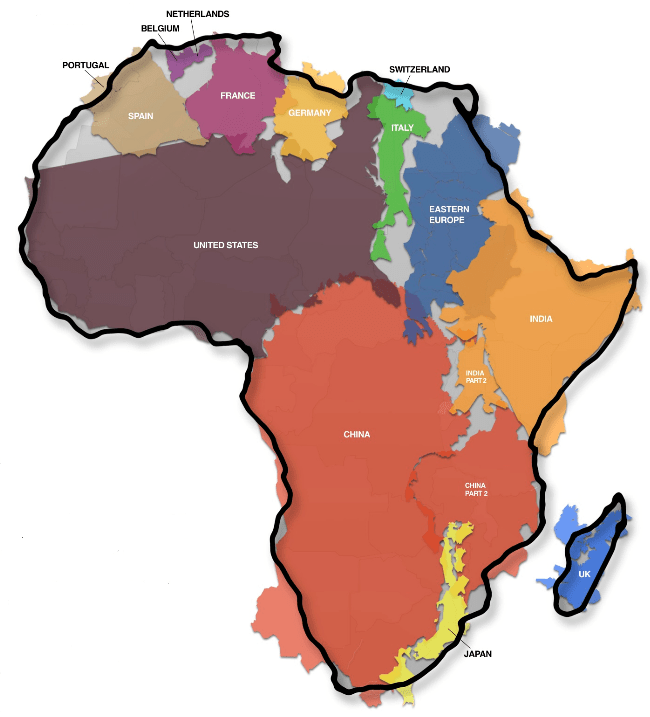

How Big is Africa?

In the second half of the Comparative World Government course we’ll be analysing issues and concepts that will allow us to learn more about the many countries located on the diverse continent of Africa. In addition to being very diverse, Africa is a very large continent. Many of us have little idea about just how big the continent is. Here’s a revealing graphic by Kai Krause, that will hopefully cure us of a little bit of our immapancy–insufficient geographical knowledge. Click on the link above to view a larger picture, with more information.

Does Africa Need a New Map?

In a recent article in Foreign Policy magazine, G. Pascal Zachary argues that it’s time to redraw Africa’s political borders, which are “unnatural” and a legacy of 19th and 20th-century colonialism. As is well-known the newly independent states that comprised the Organisation for African Unity met in 1964 and agreed that the extant international borders in Africa were sacrosanct, believing that this would best guarantee stability on the continent. It worked, to a degree. While there have certainly been very few international (i.e. inter-state) wars in Africa in the intervening 45 years, the continent has been ravaged by intra-state (i.e., internal, or “civil”) wars during the same period. What are the potential benefits of redrawing Africa’s borders to make them more coterminous with ethnic boundaries (as has been done recently in, amongst other places, the Balkans and the former Soviet Union)? Zachary’s claim:

Borders created through some combination of ignorance and malice are today one of the continent’s major barriers to building strong, competent states. No initiative would do more for happiness, stability, and economic growth in Africa today than an energetic and enlightened redrawing of these harmful lines.

How important is for for state strength and stability for ethnic and political border to be coterminous? The redrawing of borders–and it is obvious that the mechanism would be military force–would almost certainly lead to tremendous suffering and bloodshed, with competing campaigns of ethnic cleansing. But, as Zachary notes, since the start of the post-colonial era millions of Africans have died in internal conflicts, and:

Rethinking the borders could go far to quelling some of these conflicts. Countries could finally be framed around the de facto geography of ethnic groups. The new states could use their local languages rather than favoring another ethnicity’s or colonial power’s tongue. Rebel secessionist movements would all but disappear, and democracy could flourish more easily when based upon policies, rather than simple identity politics. On top of that, new states based on ethnic lines would by default be smaller, more compact, and more manageable for governments on a continent with a history of state weakness.

Assuming that the political will to achieve this goal were to evolve, what would be the best mechanism? What would Herbst’s argument be? Is this even feasible? Where would one draw the new boundaries? How would one define an ethnic group? Refer to these two maps to get a sense of the near impossibility of the task at hand. While there are about 50-odd states in Africa, there are literally hundreds of geographically-concentrated ethnic groups. In addition, there is a tremendous amount of inter-mingling of ethnic groups as well.

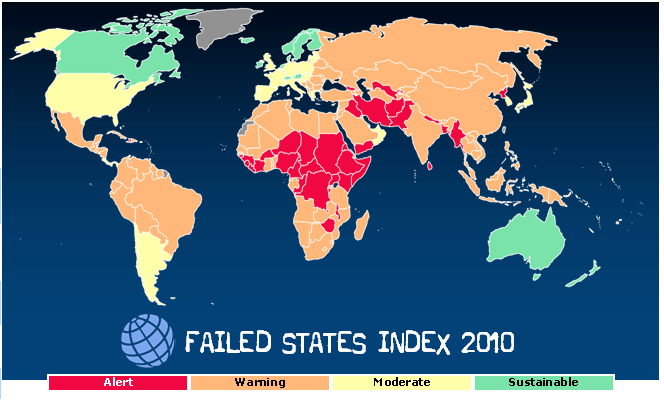

Failed States and the Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index 2010

On Thursday, September 23rd we will begin to analyse the exceptionally important concept–the state. It will become strikingly obvious that a strong state is a necessary–but not sufficient–condition for political stability, political and personal liberty, democracy, and economic well-being. Conversely, citizens living in weak, failing, or failed states face lives of economic destitution, personal insecurity (think of Hobbes’ state of nature, where life is nasty, brutish, and short), and lack of basic rights and freedoms. The Fund for Peace publishes an annual index of failed and failing states. A quick look at the results over the last decade or so finds that the same dozen or so states are continually at the top of the list of failed/failing states. Here is a map depicting the results of the most recent index:

Notice the geographical concentration of failed states (in red). Why are the vast majority of the world’s failed states found in central Africa and southwest Asia?

What are the characteristics of failed states that distinguish them from more stable states? Maybe this video of life in Somalia will provide some clues:

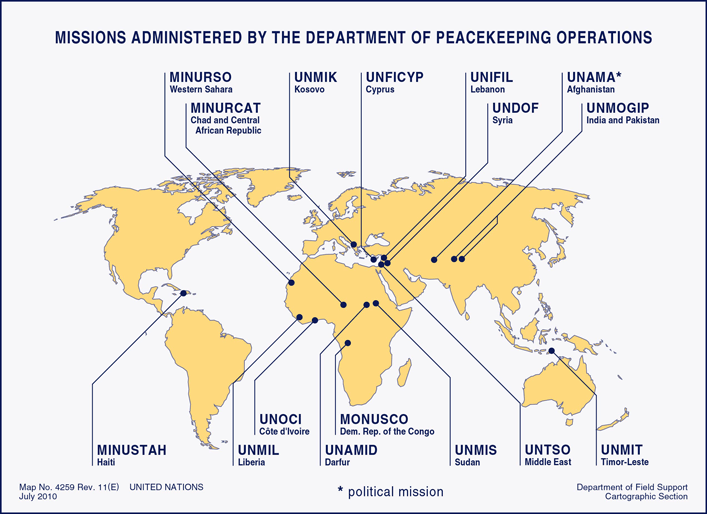

Current United Nations Peacekeeping Operations

We discussed Tom Weiss’ book–Humanitarian Intervention–in IS 302 today. We spent some time on the changing nature, and number, of peacekeeping operations since the end of the Cold War. Below is a map listing the 16 current UN peacekeeping operations. You can find the source image, which is clickable, here. How many of these operations are proceeding under the auspices of Chapter VII of the UN Charter?

Here is part of the textof the UNSC resolution, authorizing the establishment of MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

Resolution 1925 (2010)

Adopted by the Security Council at its 6324th meeting, on 28 May 2010The Security Council,

Continue reading “Current United Nations Peacekeeping Operations”

Is there a causal link between Natural Resources and Conflict?

The “resource curse” is the name given to the alleged causal links between a country’s abundance of natural resourcee and the existence of all sorts of “bad things”, such as authoritarianism, economic stagnation and/or outright economic decline, increased probability of attempted coups d’etat, etc. In our session on political economy we read Jensen and Wantchekon’s article on the link between natural resource wealth and authoritarianism, specifically, and we also looked at Richard Snyder’s article on the putative link between the existence of what he calls “lootable wealth” and political (in)stability in a state. Their conclusions were at times complementary but at times divergent. What matters (at least for political stability), according to Snyder, is the ability of the rulers (i.e., the government) to partake of the rents/riches accrued by the exploitation of the particular “lootable” resource.

Snyder’s is, of course, not the final word on the topic and there is an avalanche of published research on this very topic. A new resource that can be used to find data on the link between natural resources and conflict–political, civil, etc.–is the Resource Conflcit Monitor, maintained by the Bonn International Center for Conversion. From their web site:

Many developing countries rich in natural resources, such as diamonds and oil, have been plagued by poverty, environmental degradation and violent conflicts. In many of these countries, the natural wealth has not led to sustainable development. On the contrary, in some instances resource wealth has provided the funding and reasons for sustaining civil wars. This so-called ‘resource curse’ brought a lot of attention to the link between resources and conflict over the past decade. ’Governance’ has been identified as key factor for understanding the resource-conflict dynamic and for mitigating its negative impact in developing countries. ‘Resource governance’ in the present context describes the way in which governments regulate and manage the use of natural resources as well as the redistribution of costs and revenues deriving from those resources

The Resource Conflict Monitor (RCM) monitors how resource-rich countries manage, administer and govern their natural resources and illustrates the impact of the quality of resource governance on the onset, intensity and duration of violent conflict. The RCM serves as a tool for identifying and supporting viable resource governance and contributes to conflict prevention, post-conflict reconstruction and sustainable development….

There is an informative, and user-friendly, application that provides historical annual information on conflict and resources in individual countries. Here is the result for Sierra Leone, the specifics of which should be familiar to those of you who watched Cry Freetown. For an explanation of “resource governance” and “resource regime compliance, go here and scroll down.

There’s an additional methodological point that is crying out to be made here. Notice that the level of conflict intensity first decreases rather significantly between 1996 and 1997, then increases dramatically between 1997-1999, to then fall just as dramatically between 2000 and 2002, while at the same time “resource governance” and “resource regime compliance” do not change much at all. This means that we have to be very careful about attributing the level of conflict to the two afore-mentioned phenomena. Maybe the causal link between these two and conflict intensity is not monotonic, maybe there is a threshold effect at work, or maybe the existence of an abundance of natural resources is a sufficient (under certain conditions) cause of conflict intensity. On the whole, though, there certainlly doesn’t seem to be a clear linear, and/or monotonic relationship between resources and conflict (at least in Sierra Leone, between 1996-2006)

Resource Dependent Regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa

Jensen and Wantchekon (2000) have created an index of resource dependence and determined the level of the same for the states of sub-Sarahan Africa. The scores range from 1 (no resource dependence) to 4 (extreme resource dependence). They use this as an important independent variable in determining democratic transition, consolidation, and government effectiveness. How much of an effect does resource dependence have on each of these dependent variables? You’ll have to read the paper to find out, or attend my class in intro to comparative tomorrow.

The United Nations and Peacekeeping in Congo

In PLSC250–intro to IR–this week we viewed a documentary made by the National Film Board of Canada, which addresses the UN’s peacekeeping role in Congo. After reading Chapter 7 of Mingst, you should now be aware that the UN in the world’s most important and powerful IGO, and the UN Security Council plays the most prominent global role in the area of international security. Here are a couple of screen shots from the film and the film’s description:

Mapping the Future from CSIS

The Center for Strategic and International Studies has a fascinating new subway-style map, which interactively maps the global future on the basis of various themes–construction, sporting and culture, science, politics, etc. Each node of information on the interactive map is a hyperlink that takes the reader to a web page with detailed information about the topic.

Below is a much reduced version of the map. If you click on the word map above, you’ll be taken to the large interactive version of the map. Click on the link (which I’ve indicated using the red circle) and you’ll be taken to a page where you’ll be told the following:

As a result of the internal reorganization of the U.S. military command structure, a new headquarters dedicated exclusively to Africa is expected to become fully operational in 2008. The United States Africa Command, or AFRICOM, will report to the Secretary of Defense on U.S. military relations with 53 African countries, with a focus on war prevention and capacity-building programs. The ultimate stated goal of the program is to enable “a more stable environment in which political and economic growth can take place.” For the fiscal year 2008, AFRICOM is expected to have a $75 billion budget.

h/t to V. Wang.

The Economist’s Diary on Kenya

The eminent British magazine, The Economist, currently has a correspondent in Kenya writing up daily reports in the Internet edition, which can be viewed here. There is, of course, much to be concerned about in Kenya these days, but as an academic I found the latest dispatch especially interesting:

Morning, Professor Alan Ogot’s office, Kisumu

ALAN Ogot (pictured below), one of Kenya’s leading historians, is the chancellor of Moi University in Eldoret. Like me, he graduated from St Andrew’s University in Scotland, but he was there in the 1950s, and his life before and since has been colourful and consequential.

Mr Ogot spends the first part of our interview delving into Luo history. Contrary to their reputation among some Kikuyus and white Kenyans as agitators, he says the Luo have always done the jobs no one else wanted to do. For a thousand years they have aspired to “fairness” and “reciprocity”. He gives examples of religious and political movements to argue that Luoland was the most progressive part of Kenya. That changed with independence in 1963 and the rise of a Kikuyu elite who mistrusted Luos.

Mr Ogot had lunch with Tom Mboya on the day Mboya was shot dead in 1969. Mboya was one of several Luo politicians tipped for the presidency and Mr Ogot thinks the Luo have never recovered from his death. “What followed was a police state. We were not allowed to speak our mind.”

Then Mr Ogot moves on to the damage done to academia in Kenya by the post-election violence. He wonders what the future of research is in the country. Some of Africa’s best research institutions are located around Nairobi. Most are closed, he says, some burned, and the best minds driven out.

He points out that Maseno, the local university in Luoland, was over half Kikuyu. “Most of these people are not coming back. Who will provide them with security?” Other universities across the country are being similarly ethnically cleansed. “You call these universities? They’ll be worse than primary schools…”

…Since the election he has hardly left his house. A woman and child were shot dead outside his front gate. The police mistakenly killed a caretaker in a neighbouring house. “They have apologised, but what will that do?”

I’ve highlighted what I think are the interesting parts of the snippet I posted. First, contrary to what I have been reading in the newspapers lately, inter-ethnic relations between the Kukuyu and Luo, specifically, have not been as tolerant and peaceful and many have led us to believe. Second is the horrific damage that is being done to Kenya’s post-secondary educational system as a result of the current political situation there. A Boston Globe column that was published before the elections held out hope for Africa, and pointed to Kenya’s potential role as a leader for the rest of the continent. Now what?

You must be logged in to post a comment.