One of the leading scholars of IR theory is Joseph Nye, who teaches at Harvard University. He, along with co-author Robert Keohane, wrote one of the seminal works in IR theory–Power and Interdependence. Here is a short, but interesting TED talk in which Nye explains, amongst other things, the distinction between power transition and power diffusion, the “rise of China” and what “smart” power is.

Category: Foreign Policy

Does the Acquisition of Nuclear Weapons Change States’ Behaviour?

Political scientist James Fearon has an interesting blog post on the political science blog, The Monkey Cage. In it, he asks, and then gives an answer to, the question “How do states act after they get nuclear weapons?” The issue, Fearon notes, is gaining increasing attention in the United States, given the alleged quest by Iran to develop nuclear weapons. The issue also resonates in Canada, with Stephen Harper recently affirming his fear of the Iranian regime acquiring nukes. From this CBC interview with Peter Mansbridge, Harper responds in the affirmative to Mansbridge’s characterization of an interview Harper had given a couple of weeks earlier on the issue of Iran’s quest for nuclear weapons:

…in your view, they [Iran’s regime] want nuclear weapons, and they would not be shy about using them.[see the exchange below]

In opposition to views like Harper’s are the views of what Fearon calls “proliferation optimists” such as the well-known realist Kenneth Waltz, who claims that contrary to our repeated expectations about the behaviour of post-nuclear states, the opposite has turned out to be true much more often than not. What does Fearon find empirically? First, he sets up what it is, specifically, that he is measuring:

The following graph shows, for each of the nine states that acquired nuclear capability at some time between 1945 and 2001, their yearly rate of militarized disputes in years when they didn’t have nukes, and the rate for years when they did.

Here is a graph of Fearon’s finding with his summary below:

China, France, India, Israel, Pakistan, and the UK all saw declines in their total militarized dispute involvement in the years after they got nuclear weapons. A number of these are big declines. USSR/Russia and South Africa have higher rates in their nuclear versus non-nuclear periods, though it should be kept in mind that for the USSR we only have four years in the sample with no nukes, just as the Cold War is starting.

My Intro to IR Class is full of Realists

Last Tuesday in POLI 1140, the students completed an class oil-market exercise in which pairs of students engaged in a strategic situation that required them to sell oil at specific prices. Many students were able to understand relatively quickly that the “Oil Game” was an example of the classic prisoner’s dilemma (PD). As Mingst and Arreguin-Toft note on page 78, the crucial point about the prisoner’s dilemma:

Neither prisoner knows how the other will respond; the cost of not confessing if the other confesses is extraordinarily high. So both will confess, leading to a less-than-optimal outcome for both.

From a theoretical perspective (and empirical tests have generally confirmed this) there will likely be very little cooperation in one-shot prisoner’s dilemma-type situations. Over repeated interaction, however, learning can contribute to higher levels of cooperation. With respect to IR theories, specifically, it is argued that realists are more likely to defect in PD situations as they are concerned with relative gains. Liberals, on the other hand, who value absolute gains more highly, are more likely to cooperate and create socially more optimal outcomes. What were the results in our class?

The graph above plots the level of cooperation across all six years (stages) of the exercise. There were seven groups and what the probabilities demonstrate is that in each year there was only one group for which the interaction was cooperative. In year 2, there was not a single instance of cooperation. Moreover, it was the same group that cooperated. Therefore, one of the groups cooperated 5 out of 6 years, while none of the other six groups cooperated a single time over the course of the sex years!! What a bunch of realists!!

If you were involved in this exercise, please let me know your reactions to what happened.

“Ghosts of Rwanda” Documentary

As a video supplement to the Rwanda chapter from Samantha Power’s book on genocide, and the Gourevitch book, we viewed the first part of the PBS Frontline documentary “Ghosts of Rwanda” in class today. Please view the remaining hour or so sometime before next Friday’s class as we will use the first portion of that session to continue our discussion on the international community’s failure to halt the slaughter of more than 800,000 Tutsis by the Hutu-led Rwandan government.Here’s the first part of the documentary. Click on the video to take yourself to Youtube, where you will easily find the remaining parts.

Can the UN Keep the Peace?

Today in IS 302 we viewed the video “Can the UN Keep the Peace”, which looked at the challenges that face the UN Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like the pairing of the perfect wine with the right meal, this video was (at least in my opinion) a perfect complement to today’s readings.

William Buckely and Noam Chomsky Debate Military Intervention

Here’s a fascinating debate from the 1960s between two American intellectual giants–William Buckely and Noam Chomsky–on the morality of military intervention. Chomsky makes a very strong claim: in the history of humankind never has a state intervened military on the basis of disinterested (i.e., altruistic) motives. Military intervention is always about the furthering of self-interest, but is often dressed up in garb of humanitarianism. Chomsky notes, of course, the few exceptions; exceptions, that is, in the sense that some states didn’t even bother trying to put a veneer of humanitarianism on their naked power grabs–think Belgian in the Congo.

Michael Ignatieff and Humanitarian Intervention

Current leader of the Canadian Federal Liberal Party, Michael Ignatieff has long been involved in the issue of human rights–as a historian, journalist, public intellectual, and as the former Carr Professor and Director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Kennedy School of Government.

In the aftermath of the contentious NATO military intervention in Kosovo (1999), Ignatieff sat down with WBUR’s Chris Lydon to assess what had gone right (and wrong) during the intervention. A self-identified member of the “something must be done [to stop alleged Serbian war crimes against the Kosovar Albanians]”, Ignatieff stands by his support for the intervention, claiming that, on the whole, the benefits outweighed the costs.

Sarah Palin should have taken PLSC250

Had one of my Introduction to International Relations students been taking questions from Charlie Gibson tonight, s/he would have been well prepared to answer his question regarding the “Bush Doctrine”. As my students (still?) know, the “Bush Doctrine” was most clearly and forcefully enunciated in the 2002 National Security Strategy of the United States. While there are three major components to the “Bush Doctrine”, the most important of which (at least the one that received the most attention and presented the most radical departure from the part-realist, part-liberal, bi-partisan, pre-9/11 US foreign policy framework was the idea of using preemptive military force, without the need for there to be an imminent threat.

Democratic critics have often charged Bush and his administration with claiming that Saddam Hussein posed an “imminent threat”, but I have yet to see any evidence that anyone speaking for the administration did so. And it’s not a surprise, as the Bush Doctrine allows the use of force without imminent threat. Maybe Governor Palin should bring some of those critics along with her to my class. And if the Republican Party would like to hire a IR tutor for Governor Palin, they’ll find my rates more than reasonable.

Rising Food Prices Have Global Political Implications

The issue of rising food prices globally has come under increasing scrutiny lately and has political leaders concerned. The annual meetings of the World Bank and IMF gave prominence to the problem and newspapers and magazines are weighing in with their opinion on the potential short- and long-term implications of the dramatic spike in world food prices. Will this last? Are we finally facing a neo-Malthusian future or will we be able to find a feasible and politically palatable solution to this crisis?

The Economist has a new article on the potentially devastating impact that the rise in food prices. In an article called “The silent tsunami” the editors (who generally espouse a free-market oriented, classically liberal view of the relation between markets and the state) argue that what is needed to avert disaster are “radical solutions.”

PICTURES of hunger usually show passive eyes and swollen bellies. The harvest fails because of war or strife; the onset of crisis is sudden and localised. Its burden falls on those already at the margin.

Today’s pictures are different. “This is a silent tsunami,” says Josette Sheeran of the World Food Programme, a United Nations agency. A wave of food-price inflation is moving through the world, leaving riots and shaken governments in its wake. For the first time in 30 years, food protests are erupting in many places at once. Bangladesh is in turmoil (see article); even China is worried (see article). Elsewhere, the food crisis of 2008 will test the assertion of Amartya Sen, an Indian economist, that famines do not happen in democracies.

Famine traditionally means mass starvation. The measures of today’s crisis are misery and malnutrition. The middle classes in poor countries are giving up health care and cutting out meat so they can eat three meals a day. The middling poor, those on $2 a day, are pulling children from school and cutting back on vegetables so they can still afford rice. Those on $1 a day are cutting back on meat, vegetables and one or two meals, so they can afford one bowl. The desperate—those on 50 cents a day—face disaster.

Roughly a billion people live on $1 a day. If, on a conservative estimate, the cost of their food rises 20% (and in some places, it has risen a lot more), 100m people could be forced back to this level, the common measure of absolute poverty. In some countries, that would undo all the gains in poverty reduction they have made during the past decade of growth. Because food markets are in turmoil, civil strife is growing; and because trade and openness itself could be undermined, the food crisis of 2008 may become a challenge to globalisation.

In general, governments ought to liberalise markets, not intervene in them further. Food is riddled with state intervention at every turn, from subsidies to millers for cheap bread to bribes for farmers to leave land fallow. The upshot of such quotas, subsidies and controls is to dump all the imbalances that in another business might be smoothed out through small adjustments onto the one unregulated part of the food chain: the international market.

For decades, this produced low world prices and disincentives to poor farmers. Now, the opposite is happening. As a result of yet another government distortion—this time subsidies to biofuels in the rich world—prices have gone through the roof. Governments have further exaggerated the problem by imposing export quotas and trade restrictions, raising prices again. In the past, the main argument for liberalising farming was that it would raise food prices and boost returns to farmers. Now that prices have massively overshot, the argument stands for the opposite reason: liberalisation would reduce prices, while leaving farmers with a decent living.

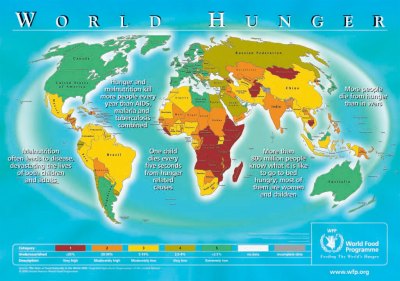

Here is a world hunger map from the UN Food Program. What do you think the various colors represent?

Pope Benedict XVI a Foreign Policy Radical

The Pope delivered a speech last week to the United Nations in which he argued–as have many radicals over the last few decades–that the will of the international community to act in order to solve important global problems is being undermined because a few states have accrued too much power. The Associated Press has more:

NEW YORK – Pope Benedict XVI warned diplomats at the United Nations on Friday that international cooperation needed to solve urgent problems is “in crisis” because decisions rest in the hands of a few powerful nations.

In a major speech on his U.S. trip, Benedict also said that respect for human rights, not violence, was the key to solving many of the world’s problems.

While he didn’t identify the countries that have a stranglehold on global power, the German pope — just the third pontiff to address the U.N. General Assembly — addressed long-standing Vatican concerns about the struggle to achieve world peace and the development of the poorest regions.

On the one hand, he said, collective action by the international community is needed to solve the planet’s greatest challenges.

On the other, “we experience the obvious paradox of a multilateral consensus that continues to be in crisis because it is still subordinated to the decisions of a few.”

The pope made no mention of the United States in his speech, though the Vatican did not support the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, which occurred despite the Bush administration’s failure to gain Security Council approval for it. At other moments on his trip, Benedict has been overtly critical of the U.S., noting how opportunity and hope have not always been available to minorities.

The pope said questions of security, development and protection of the environment require international leaders to work together in good faith, particularly when dealing with Africa and other underdeveloped areas vulnerable to “the negative effects of globalization.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.