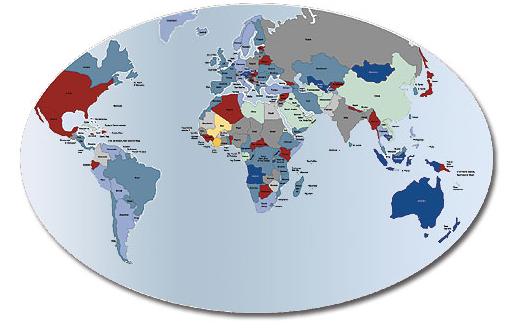

The New York Times editorial board has chosen to use its valuable op-ed space to evaluate the nature of China’s behavior on the world stage. The granting of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games to China years ago was meant to serve as a “carrot” in the carrot-and-stick approach being used by sovereign states, like the US, Canada, etc., and IGOs, like the United Nations to nudge China along the road to democratic reform and the protection of personal liberties in that communist state. Has it worked? Here’s a data point that rebuts the theory:

Six months out from the 2008 Olympics, China has jailed another inconvenient dissident. Hu Jia was dragged from his home by state police agents, and last week he was formally charged with inciting subversion. To earn the right to host the Games, China promised to improve its human rights record. Instead, it appears determined to silence anyone who dares to tell the truth about its abuses.

Mr. Hu and his wife, Zeng Jinyan, are human rights activists who spent much of 2006 restricted to their apartment. She used the power of the Internet to blog about life under detention while he wrote online about peasant protests and human rights cases.

Mr. Hu’s recent testimony, by telephone, to the European Parliament about Olympics-related rights violations may have been the last straw. Ms. Zeng and the couple’s two-month-old baby remain in their apartment under house arrest, with telephone and Internet connections now severed.

Improving its human rights record isn’t China’s only unmet commitment to the International Olympic Committee. It also promised to improve air quality. Now athletes and their coaches are figuring out how to spend as little time as possible in China’s smog-swamped capital, where they may need masks to breathe.

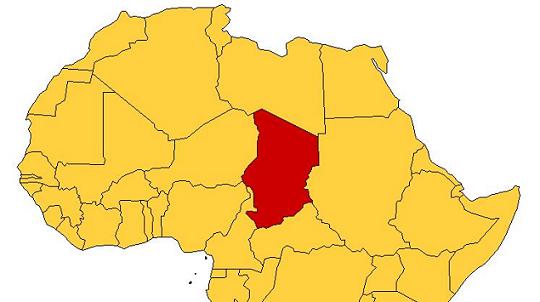

I’ve written about China before and mentioned the work of an NGO whose goal is to make the Chinese Olympics, the “Genocide Olympics”, highlighting China’s complicity in the genocide in Darfur. See this post also by one of my students in Intro to IR.

You must be logged in to post a comment.