Recent news regarding Fidel Castro’s plans to step aside in favor of his brother have returned Cuba to the news headlines here in the United States. It has prompted some to take stock of Castro’s tenure as Cuba’s leader of nearly five decades. Unfortunately, much of what we are likely to read will be ideologically-driven and devoid of much empirical substance. For a comparative look at Castro’s and Batista’s regimes, we turn to Cal-Berkeley economist Brad DeLong:

T

he hideously depressing thing is that Cuba under Battista [sic]–Cuba in 1957–was a developed country. Cuba in 1957 had lower infant mortality than France, Belgium, West Germany, Israel, Japan, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had doctors and nurses: as many doctors and nurses per capita as the Netherlands, and more than Britain or Finland. Cuba in 1957 had as many vehicles per capita as Uruguay, Italy, or Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had 45 TVs per 1000 people–fifth highest in the world. Cuba today has fewer telephones per capita than it had TVs in 1957.

You take a look at the standard Human Development Indicator variables–GDP per capita, infant mortality, education–and you try to throw together an HDI for Cuba in the late 1950s, and you come out in the range of Japan, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Israel. Today? Today the UN puts Cuba’s HDI in the range of Lithuania, Trinidad, and Mexico. (And Carmelo Mesa-Lago thinks the UN’s calculations are seriously flawed: that Cuba’s right HDI peers today are places like China, Tunisia, Iran, and South Africa.)

Thus I don’t understand lefties who talk about the achievements of the Cuban Revolution: “…to have better health care, housing, education, and general social relations than virtually all other comparably developed countries.” Yes, Cuba today has a GDP per capita level roughly that of–is “comparably developed”–Bolivia or Honduras or Zimbabwe, but given where Cuba was in 1957 we ought to be talking about how it is as developed as Italy or Spain.

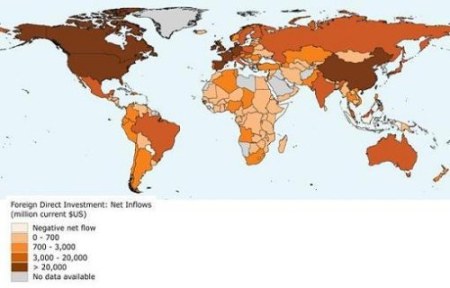

This week in intro to comparative, we’ll discuss various indicators of well-being and welfare, such as GDP per capita and the HDI, comparing the indicators themselves and comparing different countries.

he hideously depressing thing is that Cuba under Battista [sic]–Cuba in 1957–was a developed country. Cuba in 1957 had lower infant mortality than France, Belgium, West Germany, Israel, Japan, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had doctors and nurses: as many doctors and nurses per capita as the Netherlands, and more than Britain or Finland. Cuba in 1957 had as many vehicles per capita as Uruguay, Italy, or Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had 45 TVs per 1000 people–fifth highest in the world. Cuba today has fewer telephones per capita than it had TVs in 1957.

he hideously depressing thing is that Cuba under Battista [sic]–Cuba in 1957–was a developed country. Cuba in 1957 had lower infant mortality than France, Belgium, West Germany, Israel, Japan, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had doctors and nurses: as many doctors and nurses per capita as the Netherlands, and more than Britain or Finland. Cuba in 1957 had as many vehicles per capita as Uruguay, Italy, or Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had 45 TVs per 1000 people–fifth highest in the world. Cuba today has fewer telephones per capita than it had TVs in 1957.