Here’s a link to a great blog post from a POLI 1100 student of mine about political ideology and the role of the family as an agent of political socialization. Here’s an excerpt:

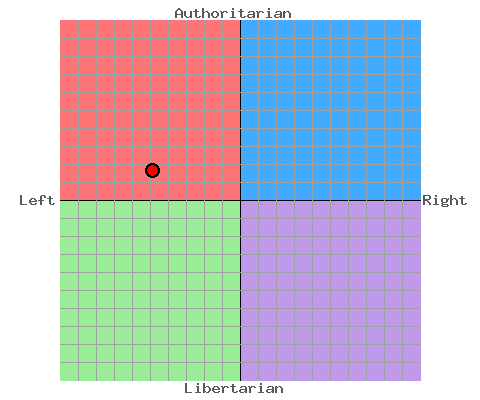

When I got my mother to take the political compass test I was sure her result was going to show that she was much more conservative that I was. I believe I thought this because whenever my older coworkers and I discuss issues that are being highlighted in the media, most of their views on those issues seem extremely conservative to me. Or at least, more conservative than that of my own…

…My mother’s ranking on the political compass, and my ranking on the political compass turned out to be almost the same. This was interesting to me because for the 18 years of my life I spent living with her, we barely said three words to each other everyday, much less discuss politics. So my political opinions were formed from other adults around me, such as teachers and my friends parents.

This is a very interesting observation. In a book I co-authored with Alan Zuckerman and Jennifer Fitzgerald, data analysis of panel surveys in Great Britain and Germany, led to some intriguing results. One of the more interesting was the role of the family matriarch–the mother–as the lynchpin in the familial political socialization process. While it is conventionally believed that the patriarch is more influential in a child’s political socialization, this was not true in our study. Mothers spent much more time with their children than did fathers (the data sets tracked this phenomenon), and it should not be surprising that, while often mothers don’t talk about politics with their children explicitly, their quotidian interactions with their children leave the latter with all sorts of clues and cues about the way to think and act about issues that are foundationally political. For example, where to school one’s child–public secular versus private parochial school–is a fundamentally political decision, yet parents may not express their reasoning for this in explicitly political terms.

Go read the rest of the blog post, and check out our book as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.