Today in class, you competed in groups to maximize total profits in a simulation called “the Oil Game.” You represented one of two competing oil producers–Iraz and Sabia–trying to maximize profits selling oil to a net importer of oil–ESYUVI (the names were created using a random letter-generator–I swear!). Most of you recognized very quickly, if not immediately, that the simulation was a modified Prisoner’s Dilemma situation. As I’ll discuss on Friday, in a Prisoner’s Dilemma situation, players acting in an instrumentally rational manner will always choose not to cooperate (i.e., “defect”), because it is a dominant strategy. What makes the situation a dilemma is that the players could do much better were they able to cooperate and trust one another.

The compelling logic of the prisoner’s dilemma, along with some strong empirical evidence, is used by realists to support their arguments regarding the nature of interaction in the international world. Liberals, on the other hand, argue that there is much more cooperation in the world than realists would predict. Thus, despite the structure of the prisoner’s dilemma, players are able to cooperate in international politics. What factors do you think make cooperation more likely? Less likely? Why?

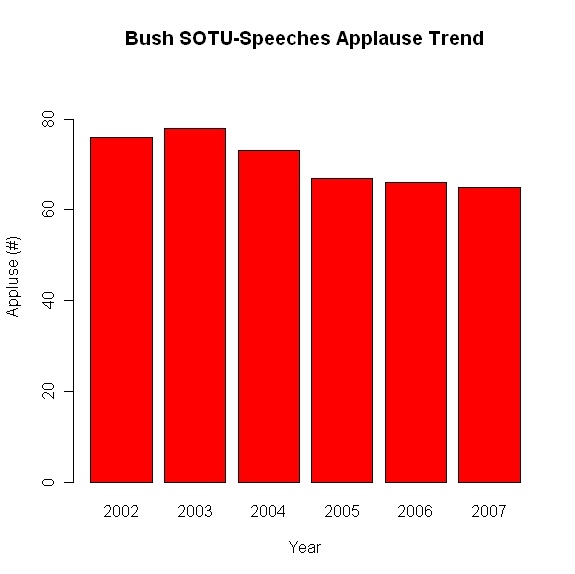

The results from our simulation today are in graphical form above. You’ll note that communication was not allowed for Years 1, 2, and 4; communication was allowed for Year 3, and communication (to decide what to do for Years 5 and 6) was allowed prior to Year 5. The results from this class are consistent with the expectations. I would note the relatively low level of cooperation throughout, rising only initially after the first episode of communication.