In PLSC250, we have discussed both Samuel Huntington’s prediction of the nature of the new world order (as outlined in his “Clash of Civlizations” thesis) and Yahya Sadowski’s response (“Political Islam: Asking the Wrong Questions”). David Ignatius has written an op-ed piece in the Washington Post today, which amounts to a book review of former CIA officer Marc Sagerman’s new book, “Leaderless Jihad.” Find some excerpts posted below. How does Sagerman’s view fit with the views expressed by Sadowski in his article?

Sageman has a résumé that would suit a postmodern John le Carré. He was a case officer running spies in Pakistan and then became a forensic psychiatrist. What distinguishes his new book, “Leaderless Jihad,” is that it peels away the emotional, reflexive responses to terrorism that have grown up since Sept. 11, 2001, and looks instead at scientific data Sageman has collected on more than 500 Islamic terrorists — to understand who they are, why they attack and how to stop them.

The heart of Sageman’s message is that we have been scaring ourselves into exaggerating the terrorism threat — and then by our unwise actions in Iraq John McCain, that, as McCain’s Web site puts it, the United States is facing “a dangerous, relentless enemy in the War against Islamic Extremists” spawned by al-Qaeda. making the problem worse. He attacks head-on the central thesis of the Bush administration, echoed increasingly by Republican presidential candidate

The numbers say otherwise, Sageman insists. The first wave of al-Qaeda leaders, who joined Osama bin Laden in the 1980s, is down to a few dozen people on the run in the tribal areas of northwest Pakistan. The second wave of terrorists, who trained in al-Qaeda’s camps in Afghanistan during the 1990s, has also been devastated, with about 100 hiding out on the Pakistani frontier. These people are genuinely dangerous, says Sageman, and they must be captured or killed. But they do not pose an existential threat to America, much less a “clash of civilizations.”

It’s the third wave of terrorism that is growing, but what is it? By Sageman’s account, it’s a leaderless hodgepodge of thousands of what he calls “terrorist wannabes.” Unlike the first two waves, whose members were well educated and intensely religious, the new jihadists are a weird species of the Internet culture. Outraged by video images of Americans killing Muslims in Iraq, they gather in password-protected chat rooms and dare each other to take action. Like young people across time and religious boundaries, they are bored and looking for thrills.

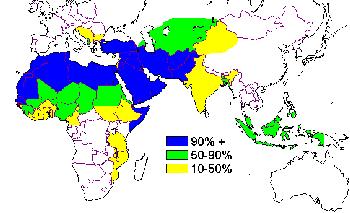

“It’s more about hero worship than about religion,” Sageman said in a presentation of his research last week at the New America Foundation, a liberal think tank here. Many of this third wave don’t speak Arabic or read the Koran. Very few (13 percent of Sageman’s sample) have attended radical madrassas.

Fifty-seven countries are not at peace with Israel today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.