In IS 302 today, we viewed the first 2/3 of the PBS documentary, Worse than War, based on the work of genocide (note: not genocidal) scholar Daniel Goldhagen , who is probably known best for his book Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Many of the issues raised by Goldhagen in the documentary were relevant to the readings of this week by Kaldor, et al.

Category: War Crimes

Michael Ignatieff and Humanitarian Intervention

Current leader of the Canadian Federal Liberal Party, Michael Ignatieff has long been involved in the issue of human rights–as a historian, journalist, public intellectual, and as the former Carr Professor and Director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Kennedy School of Government.

In the aftermath of the contentious NATO military intervention in Kosovo (1999), Ignatieff sat down with WBUR’s Chris Lydon to assess what had gone right (and wrong) during the intervention. A self-identified member of the “something must be done [to stop alleged Serbian war crimes against the Kosovar Albanians]”, Ignatieff stands by his support for the intervention, claiming that, on the whole, the benefits outweighed the costs.

Events/Lectures that may be of Interest

I’ll use this blog to keep you informed about lectures and events that may be of interest to you that are taking place on campus or in the greater Vancouver area. There are two events this week that are relevant.

This evening, Monday September 13th, at 7:00pm the Philosophers’ Cafe is kicking off the first event of its fall series at the Shadbolt Centre for the Arts at Deer Lake in Burnaby. This evening’s discussion is titled “Mixed Up: Is Canada’s cultural mix more like a melting pot, mosaic or matrix?” We’ll be addressing issues of identity and culture in about two weeks time in IS 210. The admission is $5, and the event will be moderated by Randall Mackinnon, who has served as a president, board member, executive and consulting staff for a diversity of community service organizations since 1970. For more information about tonight’s event and directions to the venue, click here.

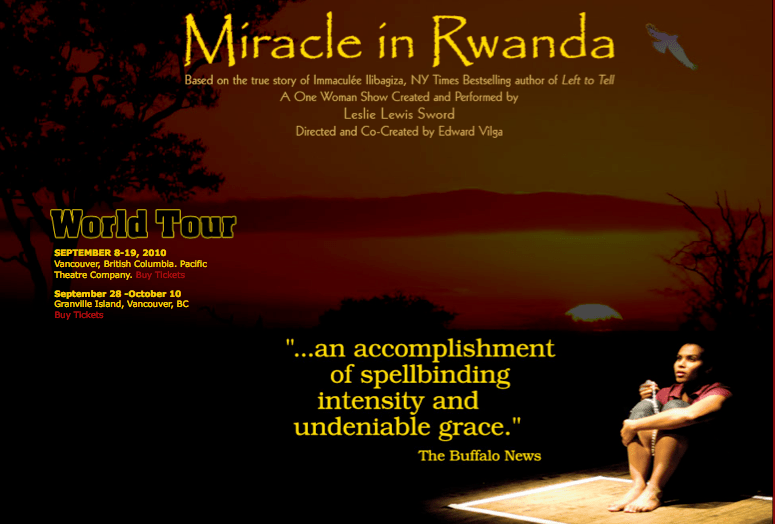

The second event is a one-woman show entitled Miracle in Rwanda, which is showing all of this week at Pacific Theatre Company and will also have a two-week run on Granville Island beginning later this month. To learn more about the show, and to purchase tickets, go here.

Update: The website I linked to above links to the wrong page. Miracle in Rwanda is part of this year’s Vancouver Fringe Festival. Here’s the correct link to information regarding show times and tickets.

Janjaweed Militia Renews Scorched-Eart Policy in Darfur

The New York Times reports that the notorious Janjaweed militia is once again active in Darfur.

Abu Surouj, Sudan, after government forces and allied militias burned the town last month. Such attacks in Sudan are a return to the tactics that terrorized Darfur in the early, bloodiest stages of the conflict.Photo: Lynsey Addario for The New York Times

SULEIA, Sudan — The janjaweed are back.

They came to this dusty town in the Darfur region of Sudan on horses and camels on market day. Almost everybody was in the bustling square. At the first clatter of automatic gunfire, everyone ran.

The militiamen laid waste to the town — burning huts, pillaging shops, carrying off any loot they could find and shooting anyone who stood in their way, residents said. Asha Abdullah Abakar, wizened and twice widowed, described how she hid in a hut, praying it would not be set on fire.

“I have never been so afraid,” she said.

The attacks by the janjaweed, the fearsome Arab militias that came three weeks ago,, were a return to the tactics that terrorized Darfur in the early, bloodiest stages of the conflict.

Such brutal, three-pronged attacks of this scale — involving close coordination of air power, army troops and Arab militias in areas where rebel troops have been — have rarely been seen in the past few years, when the violence became more episodic and fractured. But they resemble the kinds of campaigns that first captured the world’s attention and prompted the Bush administration to call the violence in Darfur genocide.

I noticed the same pattern during the wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, with militia groups acting in close concert with government support. In my study of the Croatian region of Baranya, I noticed that the villages in which civilians were killed all had one thing in common–they were on (or very near) a major regional road. This meant that government military forces (with their tanks and armed personnel carriers) had easy access to these villages, allowing the militias to swoop in and do their thing.

Peace and Punishment–An Insider’s Account of the ICTY

Marko Attila Hoare, whose blog (Greater Surbiton) is a great place to read about South East European politics, has a post on the recently published book by former spokeswoman of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), Florence Hartmann. The book is written in French and the title is Paix et chatiment: Les guerres secretes de la politique et de la justice internationales [Peace and Punishment: Secret Politial Wars and International Justice].

Hoare has a long post about the book. Here are some snippets:

[Hartmann] has used her eyewitness’s insight into the inner workings of the ICTY to support her blistering critique of the failure of the Western alliance to support the cause of justice for the former Yugoslavia. Her book paints a portrait of Western powers, above all the US, Britain and France, stifling the ICTY and preventing the arrest of war-criminals through a combination of obstruction, manipulation, mutual rivalry and sheer inertia.

One of the best parts of the book concerns what Hartmann terms the ‘fictitious pursuit’ of the two most prominent Bosnian Serb war-criminals, Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, involving repeated failures to arrest them. Hartmann gives various reasons why the Western powers might have behaved in this manner, among them the alleged agreement in 1995 between Milosevic, Mladic and French President Jacques Chirac, that in return for the release of two French pilots shot down by the Serbs over Bosnia, Mladic would never be prosecuted by the ICTY; the similar alleged agreement between Karadzic, Mladic and the US’s Richard Holbrooke in 1996, for Karadzic to withdraw from political life in return for a guarantee that he would never be prosecuted; and the readiness in 2002 of Bosnia’s High Representative, Britain’s Paddy Ashdown, to sabotage the attempts of Bosnian intelligence chief Munir Alibabic to track down Karadzic, out of rivalry with the French intelligence services with which Alibabic was working…

…Peace and Punishment, nevertheless, remains essential reading for several reasons. It reminds us that, however critical one may be of del Ponte’s performance as Chief Prosecutor, she was very far from being the only senior individual responsible for the ICTY’s failures. It gives an insight into the sort of debates and conflicts over strategy that preoccupied war-crimes investigators at the OTP. And it highlights the fact that, far from being an agent of Western imperialism, the Chief Prosecutor was acting in a frequently hostile international arena, in which she had to struggle for international cooperation, and in which the ICTY was frequently squeezed rather than supported by the Great Powers. Although, as I have indicated, I am highly critical of several aspects of this book, I would nevertheless recommend it to anyone interested in the subject of why international justice has failed the peoples of the former Yugoslavia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.