When we address Chapter 5 of Mingst, we’ll learn about the various sources of power. One of the most important, obviously, is military power. Given President Bush’s latest $3.1 trillion budget proposal, I began to wonder how much of that is apportioned to spending on the military and defense? Fred Kaplan from Slate.com has done the research and has concluded the following:

As usual, it’s about $200 billion more than most news stories are reporting. For the proposed fiscal year 2009 budget, which President Bush released today, the real size is not, as many news stories have reported, $515.4 billion—itself a staggering sum—but, rather, $713.1 billion.

Is that a lot? Is it “staggering”, as Kaplan suggests? Should we be concerned with how much we spend militarily? I think the answer is yes, but in the manner of a discriminating consumer. In other words, what is our “rate of return” on that spending? Is the spending efficient and non-wasteful? Could we be just as safe and powerful if we spent 75%, or 50% of that total? A couple of data points suggest that US military spending does not give us a good rate of return and if national defense were a private industry, we’d be looking for a different supplier. First, how does US military spending compare to how much China, Russia (two potential rivals) or the European Union, or Canada, are spending on defending their states? Here’s an estimate, from the Washington-based think tank GlobalSecurity. org (which has a lot of great data related to security issues):

|

World Wide Military Expenditures

|

|

Country

|

Military expenditures (US$)

|

Budget Period

|

|

World

|

$1100 billion

|

2004 est. [see Note 4]

|

|

Rest-of-World [all but USA]

|

$500 billion

|

2004 est. [see Note 4]

|

|

United States

|

$623 billion

|

FY08 budget [see Note 6]

|

|

China

|

$65.0 billion

|

2004 [see Note 1]

|

|

Russia

|

$50.0 billion

|

[see Note 5]

|

|

France

|

$45.0 billion

|

2005

|

|

United Kingdom

|

$42.8 billion

|

2005 est.

|

|

Japan

|

$41.75 billion

|

2007

|

|

Germany

|

$35.1 billion

|

2003

|

|

Italy

|

$28.2 billion

|

2003

|

|

South Korea

|

$21.1 billion

|

2003 est.

|

|

India

|

$19.0 billion

|

2005 est.

|

|

Saudi Arabia

|

$18.0 billion

|

2005 est.

|

|

Australia

|

$16.9 billion

|

2006

|

|

Turkey

|

$12.2 billion

|

2003

|

|

Brazil

|

$9.9 billion

|

2005 est.

|

|

Spain

|

$9.9 billion

|

2003

|

|

Canada

|

$9.8 billion

|

2003

|

|

Israel

|

$9.4 billion

|

FY06 [see Note 7]

|

Kaplan observes something even more interesting than the relative amount that the United States is spending–the apportionment of that spending amongst the different military services:

The “Overview” section of the Pentagon’s budget document contains a section called “Program Terminations.” It reads, in its entirety: “The FY 2009 budget does not propose any major program terminations.”

Is it remotely conceivable that the Defense Department is the one federal bureaucracy that has not designed, developed, or produced a single expendable program? The question answers itself.

There is another way to probe this question. Look at the budget share distributed to each of the three branches of the armed services. The Army gets 33 percent, the Air Force gets 33 percent, and the Navy gets 34 percent.

As I have noted before (and, I’m sure, will again), the budget has been divvied up this way, plus or minus 2 percent, each and every year since the 1960s [author’s emphasis]. Is it remotely conceivable that our national-security needs coincide so precisely—and so consistently over the span of nearly a half-century—with the bureaucratic imperatives of giving the Army, Air Force, and Navy an even share of the money? Again, the question answers itself. As the Army’s budget goes up to meet the demands of Iraq and Afghanistan, the Air Force’s and Navy’s budgets have to go up by roughly the same share, as well. It would be a miracle if this didn’t sire a lot of waste and extravagance.

Congress exposes this budget to virtually no scrutiny, fearing that any major cuts—any serious questions—will incite charges of being “soft on terror” and “soft on defense.” But $536 billion of this budget—the Pentagon’s base line plus the discretionary items for the Department of Energy and other agencies—has nothing to do with the war on terror. And it’s safe to assume that a fair amount has little to do with defense. How much it does and doesn’t is a matter of debate. Right now, nobody’s even debating.

Source for chart: Department of Defense

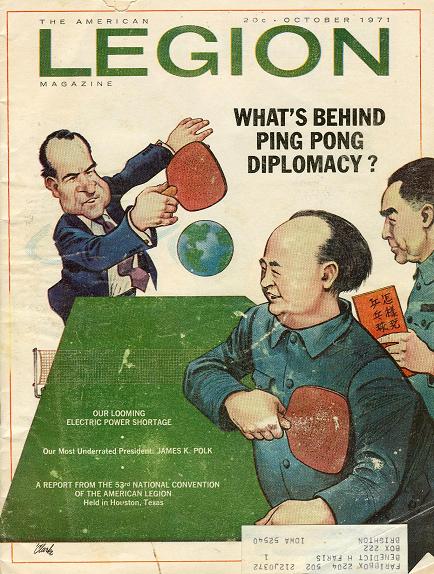

Here’s an explanation by way of example. The image below is of Richard Nixon and Mao ZeDong engaging in “ping pong diplomacy”* with Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai looking on approvingly [why is Mao using a “Western” grip?]. Those of you who know a little bit about US-China diplomatic history understand the importance of the “Nixon goes to China” moment. The most significant point, for our purposes, is that this meeting signaled the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and “Red China”, after they had been cut off due to the 1949 victory of Mao’s Communists in the Chinese Civil War. It was not surprising that it was Nixon–a Republican–who was able to make this diplomatic gesture, since it would have been politically impossible for a Democratic president to have done the same. This is because President Harry S. Truman, and the whole of the Democratic party by association, had been vilified for having “lost China” to Communism. This is the kind of “stuff of politics” that is ignored when looking at IR from only an international (or system-level) perspective. Here is a clip from a documentary analyzing Nixon’s visit to China:

Here’s an explanation by way of example. The image below is of Richard Nixon and Mao ZeDong engaging in “ping pong diplomacy”* with Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai looking on approvingly [why is Mao using a “Western” grip?]. Those of you who know a little bit about US-China diplomatic history understand the importance of the “Nixon goes to China” moment. The most significant point, for our purposes, is that this meeting signaled the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and “Red China”, after they had been cut off due to the 1949 victory of Mao’s Communists in the Chinese Civil War. It was not surprising that it was Nixon–a Republican–who was able to make this diplomatic gesture, since it would have been politically impossible for a Democratic president to have done the same. This is because President Harry S. Truman, and the whole of the Democratic party by association, had been vilified for having “lost China” to Communism. This is the kind of “stuff of politics” that is ignored when looking at IR from only an international (or system-level) perspective. Here is a clip from a documentary analyzing Nixon’s visit to China: