The issue of rising food prices globally has come under increasing scrutiny lately and has political leaders concerned. The annual meetings of the World Bank and IMF gave prominence to the problem and newspapers and magazines are weighing in with their opinion on the potential short- and long-term implications of the dramatic spike in world food prices. Will this last? Are we finally facing a neo-Malthusian future or will we be able to find a feasible and politically palatable solution to this crisis?

The Economist has a new article on the potentially devastating impact that the rise in food prices. In an article called “The silent tsunami” the editors (who generally espouse a free-market oriented, classically liberal view of the relation between markets and the state) argue that what is needed to avert disaster are “radical solutions.”

PICTURES of hunger usually show passive eyes and swollen bellies. The harvest fails because of war or strife; the onset of crisis is sudden and localised. Its burden falls on those already at the margin.

Today’s pictures are different. “This is a silent tsunami,” says Josette Sheeran of the World Food Programme, a United Nations agency. A wave of food-price inflation is moving through the world, leaving riots and shaken governments in its wake. For the first time in 30 years, food protests are erupting in many places at once. Bangladesh is in turmoil (see article); even China is worried (see article). Elsewhere, the food crisis of 2008 will test the assertion of Amartya Sen, an Indian economist, that famines do not happen in democracies.

Famine traditionally means mass starvation. The measures of today’s crisis are misery and malnutrition. The middle classes in poor countries are giving up health care and cutting out meat so they can eat three meals a day. The middling poor, those on $2 a day, are pulling children from school and cutting back on vegetables so they can still afford rice. Those on $1 a day are cutting back on meat, vegetables and one or two meals, so they can afford one bowl. The desperate—those on 50 cents a day—face disaster.

Roughly a billion people live on $1 a day. If, on a conservative estimate, the cost of their food rises 20% (and in some places, it has risen a lot more), 100m people could be forced back to this level, the common measure of absolute poverty. In some countries, that would undo all the gains in poverty reduction they have made during the past decade of growth. Because food markets are in turmoil, civil strife is growing; and because trade and openness itself could be undermined, the food crisis of 2008 may become a challenge to globalisation.

In general, governments ought to liberalise markets, not intervene in them further. Food is riddled with state intervention at every turn, from subsidies to millers for cheap bread to bribes for farmers to leave land fallow. The upshot of such quotas, subsidies and controls is to dump all the imbalances that in another business might be smoothed out through small adjustments onto the one unregulated part of the food chain: the international market.

For decades, this produced low world prices and disincentives to poor farmers. Now, the opposite is happening. As a result of yet another government distortion—this time subsidies to biofuels in the rich world—prices have gone through the roof. Governments have further exaggerated the problem by imposing export quotas and trade restrictions, raising prices again. In the past, the main argument for liberalising farming was that it would raise food prices and boost returns to farmers. Now that prices have massively overshot, the argument stands for the opposite reason: liberalisation would reduce prices, while leaving farmers with a decent living.

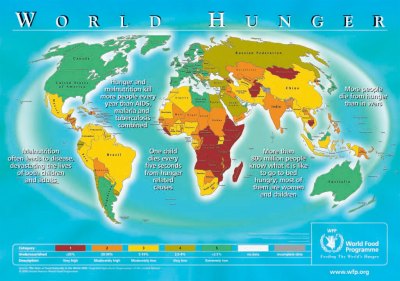

Here is a world hunger map from the UN Food Program. What do you think the various colors represent?

You must be logged in to post a comment.