William A. Callahan is a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars who is currently working on a project that links Chinese notions of self-identity and that country’s broader security environment. As you may have guessed, Callahan approaches the topic from a constructivist perspective, in which issues of culture and identity are paramount. A realist would never ask “who” is China, but “what” is China. Here’s a snippet:

Who is China? This question is fundamental to the internal debate among Chinese elites as they grapple with national identity which, in turn, affects policy decisions…culture and history are intimately linked to China’s current foreign policy outlook.

Callahan’s book project analyzes how history, geography, and ethnicity shape China’s relations with the world. “To understand this, we must look at how China relates to itself,” he said. “China’s national security is closely tied to its national insecurities.”

One such insecurity is its shame over lost territory. Callahan cited “national humiliation maps” that outline historical China’s imperial boundaries juxtaposed with present-day borders. “These maps, which are produced for public consumption, narrate how China lost territory to imperialist invaders in the 19th century—especially Taiwan to Japan and the North and West to Russia,” said Callahan. “China lost a large chunk of territory. The humiliation—and how to cleanse it—is an important point that shapes China’s nationalism and pride.”

In fact, most demonstrations in China about any given problem usually have a historical aspect, he said, such as in 1999, when the United States bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, which was viewed in China as a humiliation similar to those of a century ago at the hands of the West.

“Idealized versions of China’s imperial past are now inspiring Chinese scholars’ and policymakers’ plans for China’s future—and the world’s future—in ways that challenge the international system,” said Callahan. This makes the study of identity politics all the more critical.

China and Japan, for example, have close economic relations but cool social and political ties. Callahan said, “China relates to Japan as an evil state, recalling World War II atrocities, such as the Nanjing massacre, and this memory has taken over the relationship.”

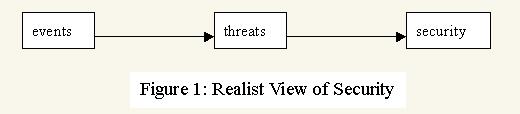

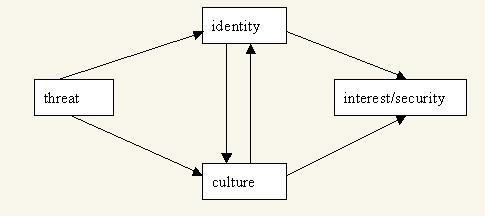

Notice the importance of the premise in the penultimate paragraph: that “idealized versions of China’s past” (i.e., culture and identity) are having a causal impact on China’s foreign policy. This contrasts starkly with realist conceptions of the nature of international relations. Below are two diagrams from Shih demonstrating the difference between realist and constructivist conceptions of security.

Notice that the impact of threats on security is not direct in the constructivist view; rather, it is mediated by culture and identity, both of which also affect each other.